AAF Board of Trustees, Founder Mirisbiris Garden and Nature Center

Share this article

Thanks to its geologic history, the new Albay Arts Center will have inspiring views of the Albay Gulf and Mayon Volcano. The rocks and the ridge underfoot began a long journey as lava erupted beneath the sea. Far, far away – several thousand kilometers away – at the southeast edge of the Philippine Sea tectonic plate! For roughly 100 million years, this seafloor inched its way northwestward, sliding beneath other parts of the Philippines (on the eastern edge of the Eurasian Plate). But as one tectonic plate plunged beneath another, parts of the ocean floor and underlying mantle got scraped off and plastered against the side of pre-existing land. Geologists call these ophiolites, from the Greek ophis (snake), because parts alter to serpentine, a rock with green, slippery surfaces. Halfway between Salvacion and Misibis Bay, opposite a view deck, serpentine is visible by the roadside. Rocks of Cagraray and Rapu-Rapu Islands, and of the AAF land and Mirisbiris, are former ocean floor, mainly pillow lavas! Just imagine! When these lavas erupted beneath the Philippine Sea, dinosaurs were roaming Asia and other continents. You won’t find any dinosaur footprints in Salvacion, but our own footprints will be on rocks the same age as the dinosaurs.

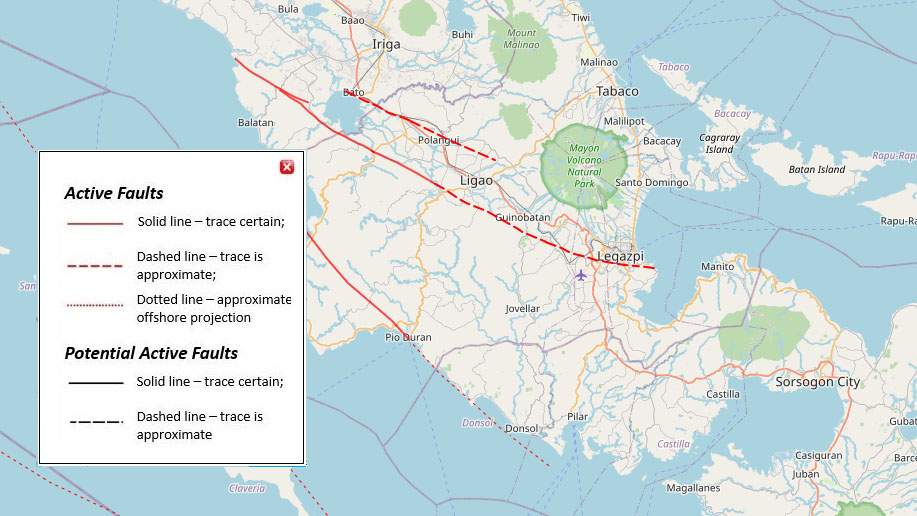

The same northwestward tectonic motion of the Philippine Sea Plate, currently at about 10 cm/year relative to the Philippines itself, is responsible for frequent earthquakes. The Philippine Fault, running from eastern Mindanao through Leyte, Masbate, Tayabas, Nueva Ecija and northwest, exists because the collision of the two plates is oblique, more like a side-swipe collision than a head-on, as the Philippine Sea plate plunges (“subducts”) to the northwest.

A splay or splinter of the Philippine Fault, the Legazpi Lineament, runs roughly along the northern side of the Albay Gulf, from Rapu-Rapu past Salvacion and across the NE foot of Mayon. The northeast side, including Tabaco, slips about 1 cm/year to the northwest relative to the southwest side, Mayon, and the Albay Gulf. There is also up-and-down motion along this fault: on its southwest side, rocks slipped downward and form the floor of the Albay Gulf; on its northeast side, rocks have been lifted above sea level, exposing once-submarine pillow lavas and creating the nice hills and panoramic views of Salvacion. Earthquakes up to about M 5 occur every few years along the Legazpi Lineament.

One more geologic consequence of the colliding, shearing tectonic plates is that coral reefs can also be lifted up above sea level. During a M 7.2 earthquake in October 2013, coral reef in Loon, Bohol was thrust 1.5 m upward, leaving parts high and dry. The same thing has happened repeatedly in Bicol, raising coral reefs above sea level, where limestone caves and our own version of “chocolate hills” have formed on nearby Cagraray Island, and all along the west side of Bicol, from Donsol to Ragay.

An additional tear or rip in the Earth’s crust created our active volcano, Mayon. This tear, connecting the Legazpi Lineament to another fault that runs from Legazpi past Libon, opens a pathway for magma to rise… over and over again. At first, there were several small leaks of magma (including Mayon, Ligñon Hill and Kawa-Kawa). When rising magma focused beneath Mayon, it continued to grow and its cousins, the other fledgling volcanoes, went extinct, destined to remain as baby volcanoes.

The Salvacion and the AAF lands are relatively safe from Mayon. In fact, during the big eruption of June 1897 (known locally as pangiri’kiti’, a crackling sound), villages at the upper end of then-Libog town were swept away by a hot blast or avalanche (uson na may lawi-lawi, or pyroclastic flow). House-sized lava bombs came to rest in Misericordia, and steep slopes above Barangays San Roque and Sto Nino mark the toe or farthest reach of some of the pangiri’kiti’ flows. Just short of the población. Another flow lobe went down the Basud River and may have reached the sea. Survivors and others scared by events bought land in what was then called Barrio Bulo and, thankful to have survived, renamed it Barrio Salvacion. Some moved here; others kept the land for possible evacuation. Much of the land of Salvacion was once state or friar land, then bought by families from Libog town who kept it for coconuts and as a safe fallback during eruptions. Bikal High School, near the AAF land, becomes an evacuation site every time Mayon threatens.

Art and science are sometimes said to be totally different spheres. Artists are creative; scientists are geeks. I don’t think so. Many geologists savor the beauty of nature, reflect humbly on our own brief time in evolution, and appreciate the arts as a way to celebrate the wonders of life. Even in the aftermath of a destructive volcanic eruption, there is art in recovery, led by nature, by storytellers, and by those who can capture scenes of the day for future generations to ponder. Rocks tell their stories, and creative geologists interpret and repeat them!

Chris Newhall is a American retired geologist who has resided in Albay for the past decades. He and his wife own and run Mirisbiris Garden and Nature Center.

A vibrant cultural center for visual, performing, and literary arts in Albay province.

Established 2022. All rights reserved.

For information about being part of the AAF community, email us here.

We care about your digital security. Read the AAF Privacy Policy.

A vibrant cultural center for visual, performing, and literary arts in Albay province.

Established 2022. All rights reserved.

For information about being part of the AAF community, email us here.

We care about your digital security. Read the AAF Privacy Policy.